Thoughts

Generative Design Through Selfies: A Video Research Method and Tutorial

Twenty-five years ago, I learned a "right way" to conduct generative, qualitative research: go to the place people work and live, establish rapport, become an apprentice, and ask open-ended questions.

Recently, I've found a passion for a different approach: a Selfie Study. This is an entirely remote-based method that combines cultural probe-style interventions with participant-created content. Participants receive daily text messages, and respond by recording themselves doing things. The method runs contrary to a lot of what I've held true about research, primarily that being physically present in context was an axiomatic part of being empathetic during and after research.

Here are some examples of how we’ve used Selfie Studies.

Buying insurance on the treadmill

We recently worked with a very old, very conservative life insurance company. The company was hoping to better understand how families made decisions around purchasing complex products like Whole Life Insurance. The very old and conservative company has very old and conservative executives, who were convinced that families get together, sit around the dinner table at a meeting, and have a serious conversation around life, death, and wealth. If such a meeting actually occurred, it would prove to be impossible to attend it first-hand, so we recommended and successfully deployed a Selfie Study.

Turns out that life insurance purchasing is not the serious decision it was believed to be; it was treated extraordinarily casually, driven in many ways by the simplicity that newcomers in the space, like Lemonade, have made the purchasing process, and by the changing norms of society at large. One of our participants researched and made the decision to purchase life insurance on the treadmill at Gold's Gym, and watching this video completely blew the collective minds of our stakeholders, paving the way for a fundamental shift towards new, casual, digital-only purchasing.

Managing the chaos of four children

We also recently deployed a Selfie Study with parents of young children, to understand what the idea of early childhood education means to them. In the past, our study might have entailed a three-hour visit with the parents, a seat at their kitchen table, and a guided interview. In this Selfie Study, we sent them two prompts each day via text message, and asked them to video themselves completing a task or answering a question. An example task was to show us their children's most educational toy, and explain why it was valuable.

The responses were candid, and provided insight not only into their toy selection, but into a wide variety of their perspectives on education. We learned about why they trust to teach their children ("This is the television, where we watch Miss Rachel, to whom we owe our lives"), how their socioeconomic circumstances impact how their children learn at home ("This is a Speak and Spell that we were given at the church; it's the most expensive toy we have"), and their values about technology ("This is our backyard. It's the most educational toy we have. I want my kids as far away from electronics as possible.")

We learn a lot from what our participants say. We learn more from the context of each video. Affluent product managers often have beautiful, clean, structured homes with partners and at-home caregivers to help provide their children with a strong foundation for learning; they have expensive toys and devices, and read countless books on the most effective ways to structure educational experience.

When this study was over, these product managers watched videos of everyday people, living in what one of our clients, after viewing the videos, described as "perpetual anarchy"—children, toys, television, noise, and chaos, everywhere. It's one thing for our stakeholders to read the transcript of an interview with a single parent describing living in a one-bedroom apartment with their four children. It's entirely different for them to watch that parent, in real-time, breastfeeding one child, disciplining another, calming a third, and teaching a fourth with the flashcards they made themselves, because they couldn't afford the store-bought ones.

Texts, to prompt behavior

Selfie Prompts are texts we send to our participants to provoke their behavior and their recordings. These are short messages that describe what we want our participants to do, and how we want them to do it.

Here's an example prompt that we used in the education study described above:

Good morning Sarah! This morning, I would like you to think about the place in your house where you feel your child learns the most. Take me on a short tour of the space, and when you're done, upload your video here: [link] Please complete this activity by 2pm, and text if you have any questions. Have a great day

There are a few parts of the prompt that are important.

First, the prompt is casual, using pleasantries like "Good morning," "Have a great day," and emojis. It's important that the participant views us as part of the regular cadence of their life, not as an inconvenience or imposition, and these types of normal text elements are familiar. We change our tone for younger audiences, occasionally using shorthand text that might be more familiar to them.

We're consistent in our tone throughout the study, so each participant understands they are interacting with one single researcher, and we reinforce that personal tone by using a first-person reference ("I would like," "Take me on a short tour...") And we offer ourselves for help, through text.

We have some pragmatics in the message, like a deadline and a place to upload the video. We've already described deadlines and the file sharing tools we are using to our participants during a pre-interview, but we reinforce them in each text.

The most important part of the prompt is the request for action. This request needs to be extremely short and directed, without unnecessary language or qualifiers, and focused on action rather than conversation. Phrases like Show us or Demonstrate or Let us see an example lead to rich, powerful and thorough views into participants' lives, while more introspective instructions like Discuss or Explain can lead to thinner, shorter and less engaging responses. Participants respond well to two prompts per day (one in the morning and one in the afternoon), and remain engaged in the process for as long as a week with the correct incentive and prompts.

The acceptance of the selfie

In the past, my team would have depended on retrospective accounts for our insurance purchasing, and on photographs, audio recordings, and transcripts of our educational sessions in people's homes; this would have generated solid, actionable data. But I've found that it's nothing compared to video, and particularly, the blurry, shaky, first-person, interrupted, messy, poorly lit, and real selfie.

We first tried video diaries about a decade ago, and it was rough. Participants were nervous of taking videos of themselves, and the results were cold, impersonal, and lacking the expansiveness of a contextual interview. Participants struggled with saving and uploading videos, and many participants didn't text on a regular basis and so they had difficulty receiving and acknowledging our text message prompts. Additionally, our clients themselves were less familiar with the medium, and skeptical of the process.

But a lot changes in ten years. Society at large has learned to welcome video into our lives and homes and offices in such an integrated, open way that selfie-nervousness has become a non-issue. We've gotten comfortable sharing intimate parts of ourselves with strangers. Covid made even the most technically avoidant of us somewhat capable using devices and software. Even those of us who are camera-shy have gotten used to seeing ourselves on screen. And many of our clients are, themselves, on sharing platforms like TikTok, sharing intimate videos of their lives and families.

The rawness of the data is the key

Traditional design research generates presentations and spreadsheets and write-ups. These are tools that sterilize human behavior to fit into a corporate context. Selfies break that mold. The reason a Selfie Study is effective is because it provides a raw, intimate view into people’s private lives. I’ve been surprised to see the most quant-driven clients forgot about a sample size of one when they view an out-of-focus, crass video of someone’s living room. Selfies are a form of acceptable voyeurism, and they give us an emotional tether to our customers that’s really unlike any traditional market or design research methodology.

A Tutorial For Running a Selfie Study

I invite you to learn from our mistakes when you conduct your first Selfie Study. This is a comprehensive tutorial on how to build, deploy, and manage a Selfie Study, based on our lessons learned in bringing this type of methodology to client projects.

For the sake of the tutorial, I’ll assume you already know the fundamentals related to qualitative research, such as participant screening and good interviewing techniques. I’ll focus instead on the things that are truly unique to this method, which are primarily related to managing the complexity of lots of small, moving pieces.

Getting set up: being organized

This method demands a level of methodical rigor that many designers just aren't used to. We've learned the hard way that, without this rigor, you'll struggle to make sense of hours of video. But with this overly structured approach, you'll be able to manage a complex study, make sense of the data, and leverage video to share your findings with your extended team.

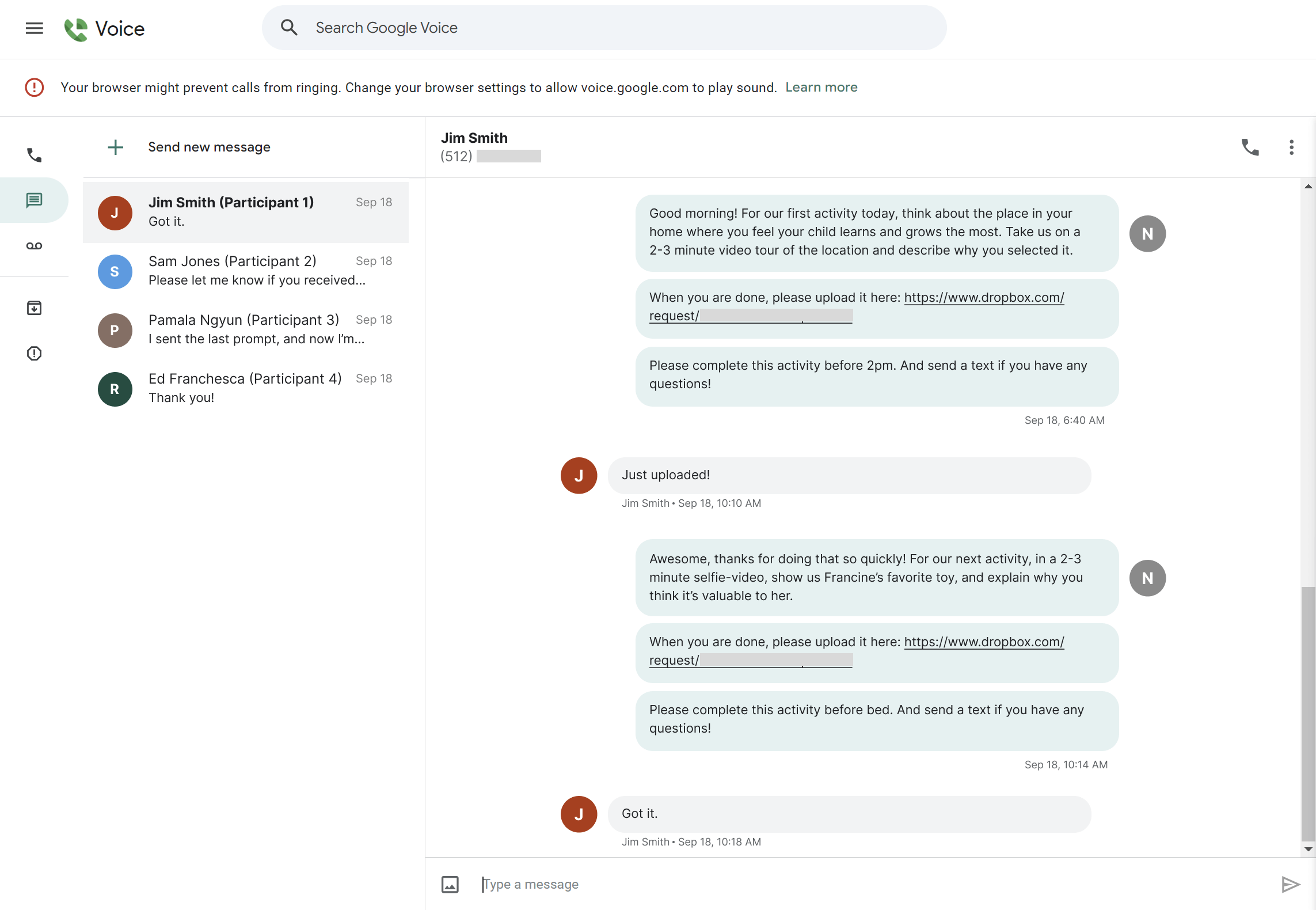

Shared Google Voice setup

One of the first things we establish is our tool for chatting with our participants. We’re in constant communication with our participants, much more frequently than in a traditional contextual interview. We use Google Voice to manage this communication; Google Voice is a platform for sending and receiving text messages on a web and mobile device. A key benefit of the tool is that the whole research team can see a single log of the texts and calls that have gone back and forth between a researcher and a participant. It provides privacy for the research team: there’s no need to offer our personal cell number to our participants. And it makes it easy to text directly from a laptop, so you can respond instantly to a participant’s questions or messages.

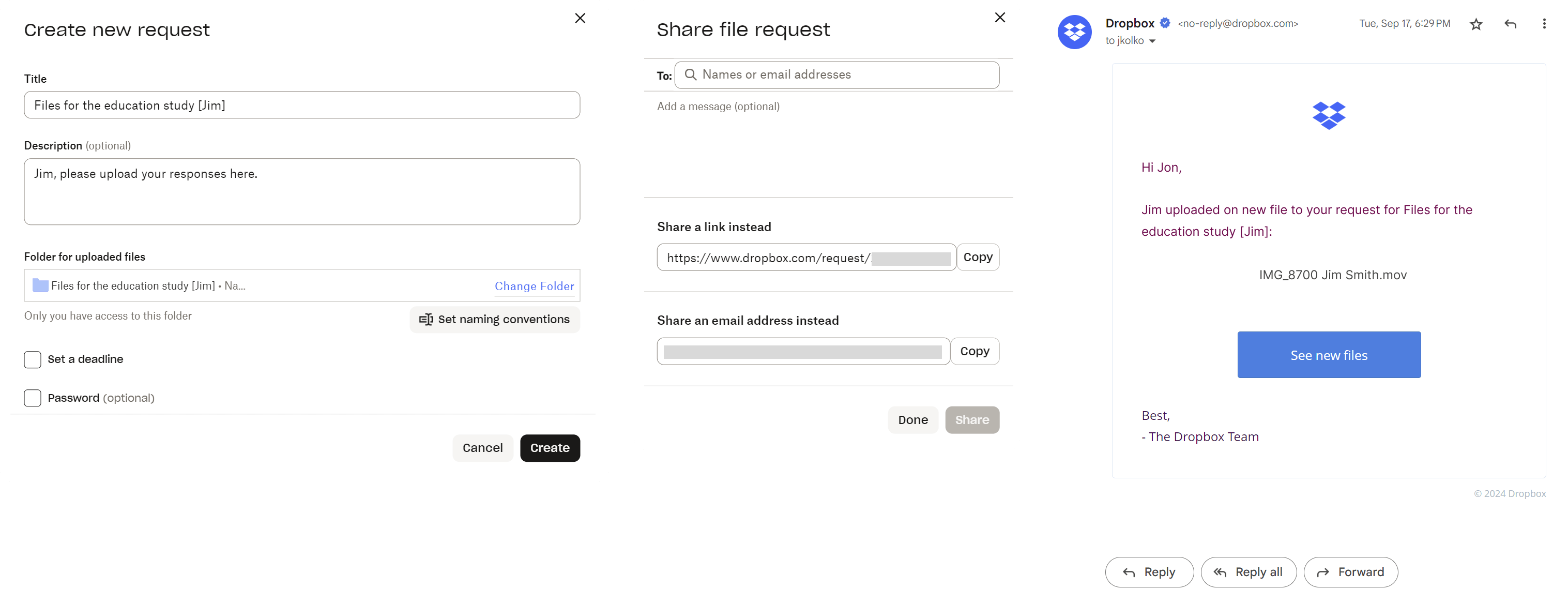

Dropboxes

Our participants are going to film videos; then, they’ll need to transfer it to us. Using text and MMS results in degraded quality of the video returns, to such a degree that the contents are unusable. We use Dropbox's File Request capabilities as a way for participants to send their Selfies to us.

Rev connectivity

We need solid transcriptions of the videos the participants generate. In a formal interview, we’re armed with a high-quality audio recorder and we can often find a quiet, isolated space for our conversation. This means we can use automated or AI-driven transcriptions. With a Selfie, the audio quality is typically poor. We use Rev to receive human-created transcriptions. Because the videos are very short, we typically receive transcripts in under an hour. And Rev connects seamlessly to Dropbox, so we can easily upload our Selfies and receive our transcripts.

Recruiting, screening, and scheduling

The recruiting process for a Selfie Study is similar to other research approaches; we develop a screener, find a source of participants, and then work to identify matches representative of the research targets. There are, however, a few notable differences.

First, the research study follows a unique format, and it’s likely that participants have never experienced a study that requires their engagement over time. After determining that a participant is a good fit, they need to really understand how the study will work, and what their time commitment will be. This means discussing the process several times, and being explicit about when each touchpoint will occur and how long it will take.

Additionally, participants need to understand that they will be taking video of themselves, their homes, their workplaces, and potentially their family. We expected this to be a point of attrition, but we’ve never had a participant abandon the study when learning about this requirement. People feel comfortable bringing video into their homes—and are much more comfortable than they are bringing a researcher into their homes!

Like most studies, we have participants sign consent forms that inform them of what they will be asked to do, and how we will keep their information private. Our attorney added a new twist to the document. Since participants will be content generators, they need to also assign copyright, ownership, or explicit rights to the materials they make. We explain the consent form in detail during our screening and scheduling process; this was another aspect to explain and make sure participants understood.

Finally, our participation compensation is increased dramatically for Selfie Studies. While the amount of time the participant provides is approximately the same as an in-person interview, the duration is spread over a week, and requires more intrusion into their day to day lives. We’ve found that compensation of $350 per participant is appropriate for a week-long study.

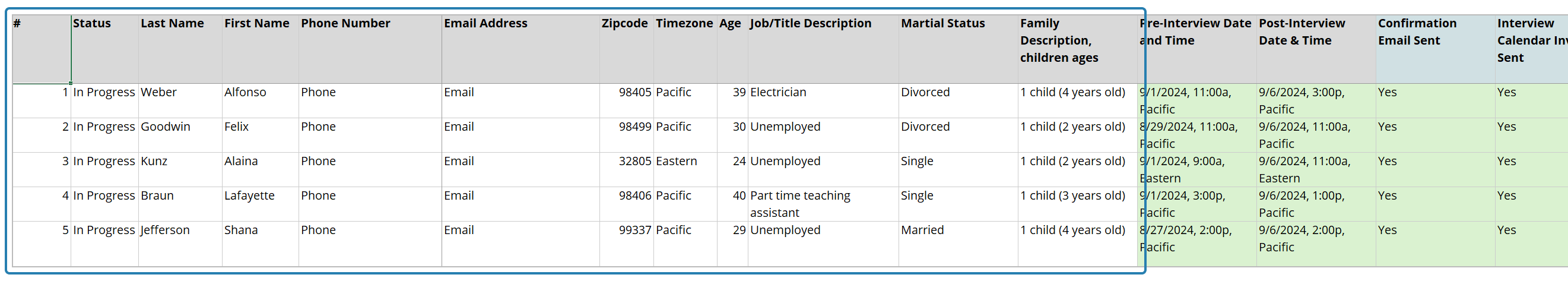

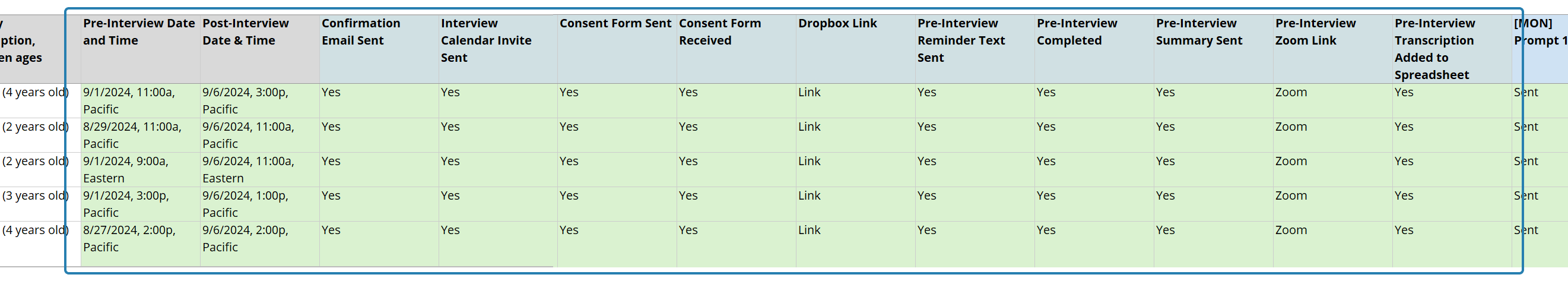

Preparing to track the process

As boring as it is, a comprehensive tracking spreadsheet is the key to holding together a study. Here's how we set it up.

The first set of columns in the spreadsheet includes meta-data about each participant. We track the basics—participant number, first name, last name, and other basic demographics. Unique to this approach, we also include phone number and email address so we can remind participants if they forget to respond to a Selfie Prompt. We also include the timezone, so we can make sure we’re sending prompts at an appropriate time of day.

The next set of columns relate to things that happen before the Selfie Study begins. This includes information about the pre-interview (more on that later), as well as confirmation tracking. We send an email confirmation when a participant has agreed to participate which includes the time and date of their pre-interview, and that reiterates how the study will work. We also send a consent form via Docusign, and a calendar invite for their pre-interview. There are columns to track the status of each of these items. We anticipated Docusign to be difficult for participants. It isn’t; they have no trouble receiving, reading, and agreeing to the consent form via that tool.

We have a column with the unique Dropbox link each participant will use to return their Selfie prompts; we use this same link in each Selfie Prompt we send via text message.

The day before the pre-interview, we send a text reminder, and we track that here. When the pre-interview is over, we track the completion status, and include a link to the Zoom recording. We have a column to make sure the interview has been sent for transcription, another for when the transcription has been received back, and another for when it’s been integrated into the utterance spreadsheet (more on that below.)

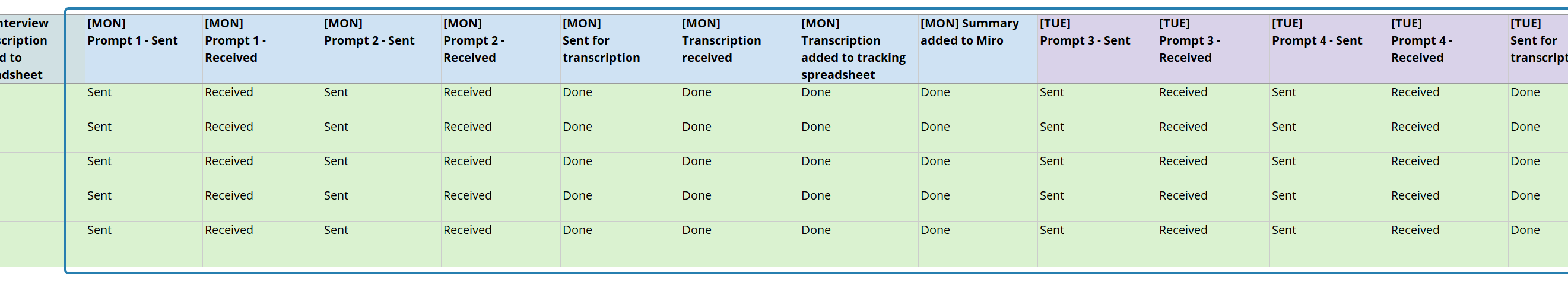

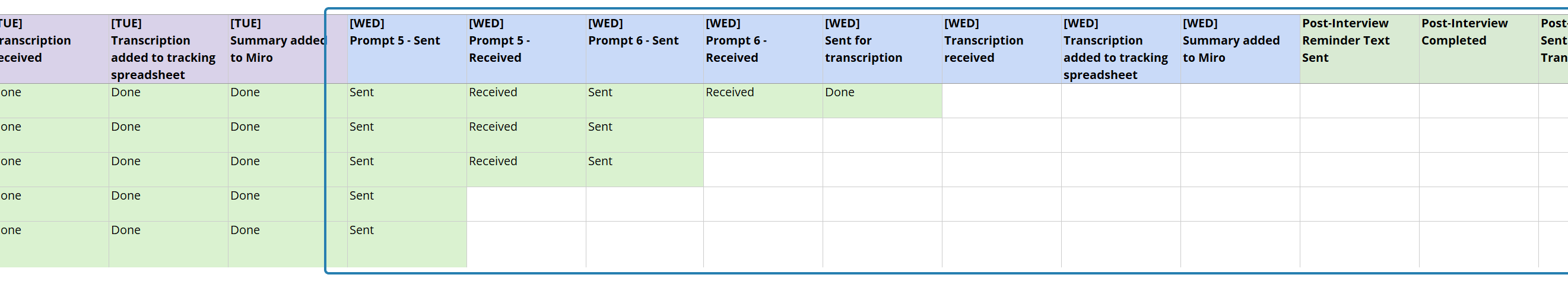

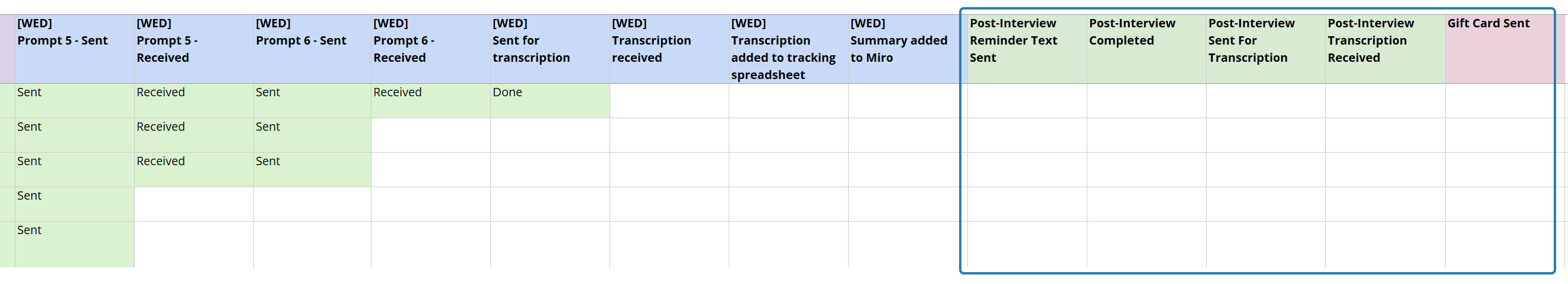

The most important part of the spreadsheet is tracking when the Selfie Prompts have been sent, received, and processed. We include a column for each of these attributes, and for each prompt.

The visual nature of the spreadsheet makes it easy to see which parts of the process are complete, and which are still in motion.

Finally, we track the post-interview—the conversation we have when the Selfie Study is over—and make sure that it’s been recorded, transcribed, and added to the various tracking documents.

Creating the spreadsheet is important, but actually using it is critical. I’ve observed that even having a spreadsheet on the screen can give designers anxiety, as it’s just not a tool they feel comfortable with. But as you’ll see below, the process can become overwhelming very quickly, and keeping the spreadsheet up to date is the key to holding the whole study together.

Managing the process

Initial interview

During in-person interviews, we often spend the first portion of the interview asking open-ended questions about the participant. This serves as a baseline of understanding about their context, but also establishes a strong rapport, quickly. We smile, laugh, are often self-deprecating, and ensure that the participant realizes we're there to learn, not judge.

During a Selfie Study, we substitute that in-person conversation for an initial 30 minute Zoom interview. We include the similar baseline research questions ("Tell us about yourself", "Tell us about your family"), and try to build the same rapport as we would in-person. But we also use this interview for some other main objectives.

First, we use the pre-interview to assess how comfortable each participant is with technology. Are they able to download and use Zoom? Did they figure out how to turn their camera on? How's the quality of their audio? What can we expect from their lighting?

We also use the interview to understand how likely they are to participate, fully. Even though we send a calendar invite and a text reminder, did the participant remember to attend the meeting? Were they late?

The interview is another opportunity to remind the participant of the cadence they can expect of text prompts, and to reinforce the expectations: that each prompt will have something to do and record via video, and will be due at a certain time of day.

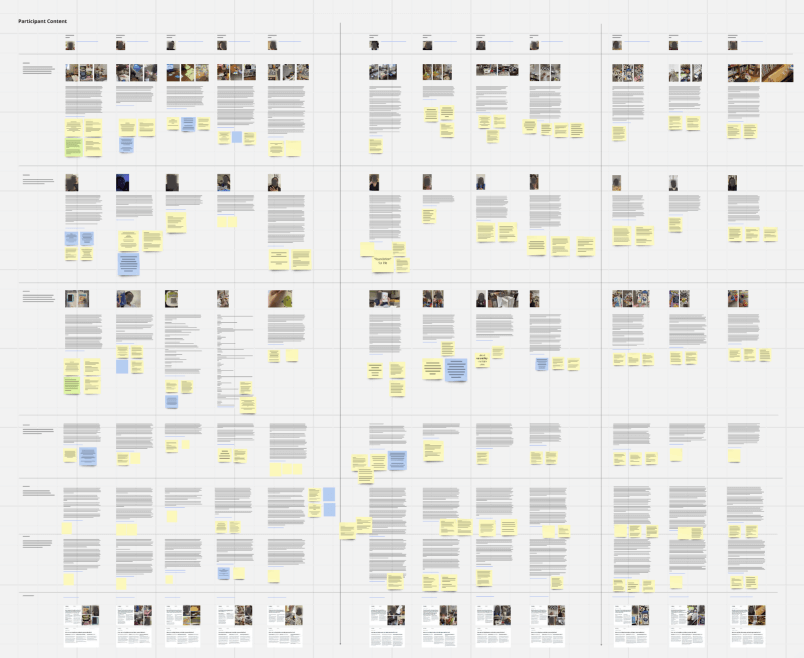

Leveraging a shared Miro canvas

As is true with most design teams, we’ve been using shared workspaces, such as Miro and Figjam, to provide war-room style canvases to share and explore data, both in our team and with our clients. This form of canvas works extremely well to summarize and share data related to the Selfie data. We use this as an organizational and analysis tool, not a synthesis tool, and we set the canvas up centered around each participant.

First, we extract a great image of the participant, and use it as a header element. We try to pull a still that captures their demeanor and body language. This helps us keep track of participants, but also acts as a grounding element for the data that will follow: it reminds us of some of the subjective and contextual qualities that frame their answers, and it even helps us better “hear” their voice when we think about them.

Next, we identify key utterances from the pre-interview, and include those at the top of the participant’s section. We try to limit these to three or four main responses that exemplify the context of each participant’s life and experiences—the things we learned during the pre-interview that most shape how they work and live, and that most impact their values and behavior.

On the majority of the canvas, we include the data generated by the Selfies. This includes visual excerpts from each Selfie, a full transcription of that response, and a direct link to the video on our Dropbox. Because the responses are much shorter than a full interview, it’s manageable for a team member to read the entire Selfie transcript quickly, and that including it in full, in combination with the imagery, is the best way to prompt quick recall.

We’ll continue this process of creating Selfie blocks, pulling out key stills, and including the transcript and video link for all of the responses, and across all participants. When we’re done, we’ll have a single canvas representing the breadth of the study.

A note on using an online tool; we continually backup the canvas in the format of the tool, and in a generalized format (such as a .png or .pdf file), and store those backups on our Dropbox. Most of the online tools have a history, but they can be extremely cumbersome to use, and more importantly, using a tool’s history relies on the internet behaving and the tool being available online. A synced Dropbox with a local copy of a .pdf means we can leverage the content quickly without relying on a third-party.

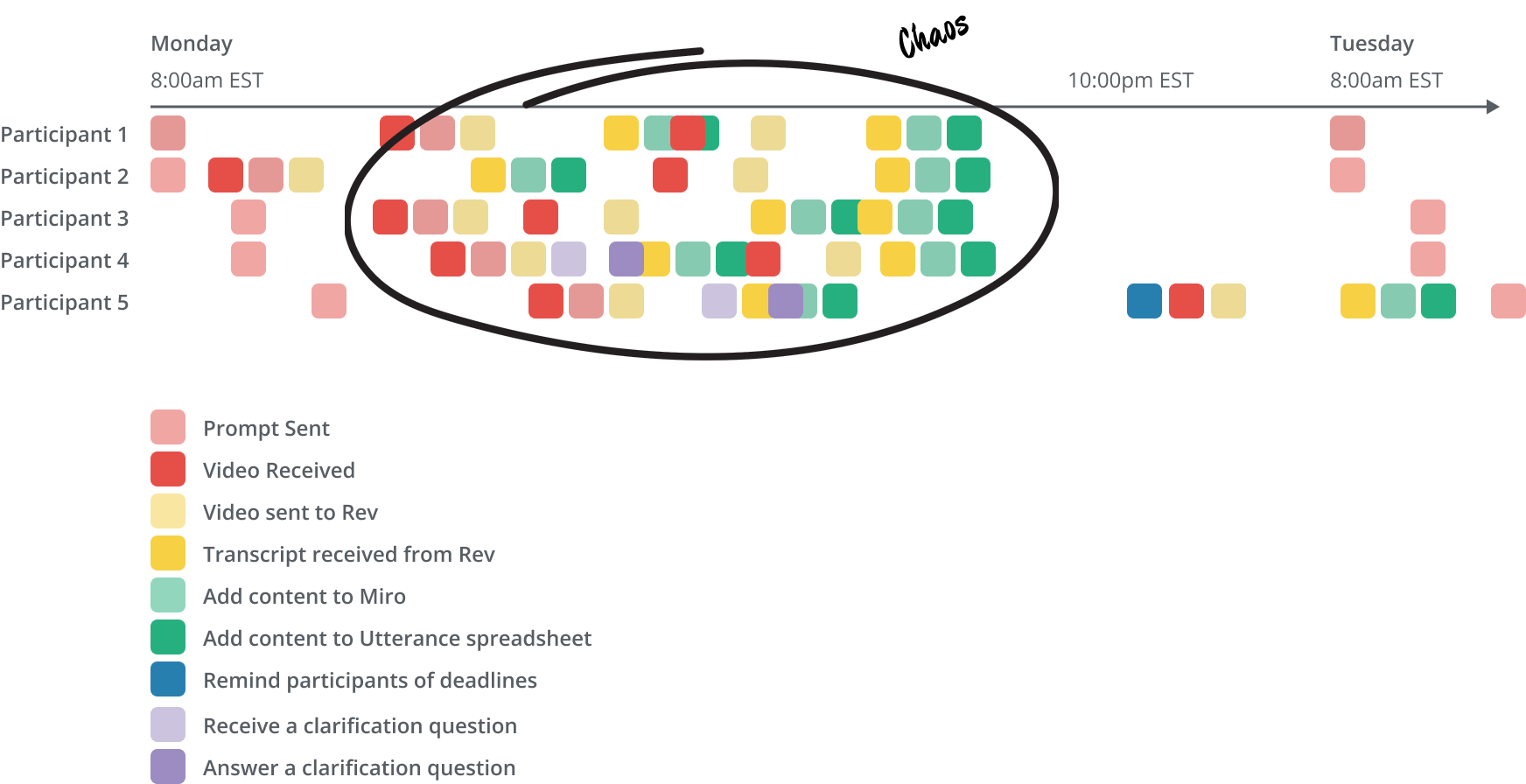

The hardest part: Your day-to-day of prompt delivery, reminders, transcription, and file management.

Anyone who has conducted field research knows how exhausting it can be. Most of your day is spent driving between participant’s homes or offices, catching up on email at Starbucks, and juggling last-minute schedule changes. A Selfie Study is a different form of exhaustion, one that took me by surprise when I managed my first study: it's a feeling of being in a whirlwind, always being incomplete and disorganized, and constantly trying to stay ahead.

The most important part of running the study is managing the delivery of text messages to participants, because these text messages prompt them to record their videos. In our studies, we send a prompt in the morning and in the afternoon. The two prompts are different, and we customize the messages with our participants names ("Hi Jon! For our next prompt..."); this means we need to make sure the right message is going to the right person at the right time.

We give our participants a deadline each day. We ask for the morning prompt to be returned by 2pm, and the afternoon prompt to be returned by bedtime. Some participants respond right away, while others waited until the deadline. We send prompt 2 immediately upon receiving prompt 1, to give participants the maximum amount of time to work on it. So, while morning prompts are sent all at once, the dissemination of afternoon prompts is staggered.

Sometimes, participants miss their deadlines. This means we need send a reminder, again customized with the person's name. And, as the day grows later, we send pre-reminders to ensure people engage before going to sleep for the evening.

Each time a video is returned, we receive notification from Dropbox. This kicks off a manual transcription process: we rename the video, upload the video to Rev for transcription, and add our Dropbox link to our Miro board.

Each time Rev completes transcription, we kick off another manual process: renaming the transcript, adding it to Dropbox, embedding the transcript in our master utterance spreadsheet, and embedding it in our Miro board.

As the week comes to an ends, we conduct our pre-interviews with our next set of participants, and we schedule and then hold our final interview with our current participants. Each of these steps requires communication and tracking.

A given day looks like this:

- Send five morning prompts.

- Receive a notification from Dropbox that a participant has completed and uploaded a Selfie.

- Send that participant the second prompt, and indicate in the tracking spreadsheet that the video has been returned.

- Begin the Dropbox-to-rev process.

- Receive another video from a second participant, while still managing the first. Send them the second prompt, and begin managing their response, just like participant one.

- Receive a question from a participant via text, asking for clarification on what they’ve been instructed to record.

- Begin to answer, and while responding, receive an email notification from Rev indicating that the first transcript is ready.

- Receive another Selfie video.

- Begin to move the Rev information into Miro.

- Receive another Selfie video.

- Send reminder texts about morning prompts to participants who haven’t responded yet.

- Manage incoming responses to the second prompt, will still managing content from the first prompt.

This continues all day, each day, for the duration of the study; at the end of the week, add

- Send reminders to the next group of participants, reminding them of the project kickoff

- Send reminders to the current group of participants, reminding them of the upcoming final interview

- Synthesize the information coming back from participants: read the transcripts, watch the videos, and start to conduct traditional sensemaking activities of theming, insight development, and stories from the field.

It’s one of the most mentally exhausting processes I’ve had to deal with while managing a design project. During a study, I have a constant feeling of being in a tornado, and I liken it to the operations of an airport. At an airport, each day starts as planned. All of the planes are where they are supposed to be, waiting for passengers. The day starts, and a pilot is late. The next plane is delayed, people miss their connections, and each thing that happens impacts the next. The chaos of the day balances precariously on the edge of control. As the day winds down, the planes eventually find their way to where they are supposed to be, and by the end of the day, everything is back to normal. Then tomorrow, it all happens again.

This is why keeping, and actually using, the tracking spreadsheet is so important. I recommend updating the sheet every time you complete any step, because it’s inevitable that you’ll forget who you responded to, who needs to receive a prompt, and what data has been processed.

Post-interview

The last step in our Selfie Study is a one-hour post interview. We use this interview to ask follow-up questions on what we observed, both individually and as a summary of all videos taken. It’s a fairly standard interview, but requires unique preparation, as we need to relate the questions to the specific Selfies the participants have created.

We include a “gap day” between the last set of prompts and the post-interview, to give our team time to structure the interview script for each participant. As with the rest of our process, we use Miro to organize the questions for the interview, and add questions to the board all the way until the post-interview begins.

Data management

Cataloging in the utterance spreadsheet

We use a spreadsheet to catalog all of the transcribed utterances, from all of the participants, and include both their pre and post interviews as well as their Selfie responses. I’ve written before about how to build this spreadsheet, and it’s not materially different here, but there are some adjustments.

We include a reference to the specific Selfie, so we can quickly find the right file when we need to review the data. We also leverage time-stamping more aggressively. When we only have a single video interview to manage, it’s fairly quick to identify the part of the interview we want to pull as an excerpt, and then extract that to use in a presentation. But since we’re going to be building more collage-style videos, having very precise time stamps become much more valuable. Rev provides this, and we pull it into the spreadsheet along with the other information.

We use the utterance spreadsheet as a way of quickly finding content related to themes, driven by keywords. When we synthesize data and discuss a particular topic, we can Ctrl-F to remind ourselves of when that topic was mentioned by our participants. Additionally, we use the spreadsheet to pull more comprehensive quotes in our documentation—a single utterance, split on a line break, may need the language that comes before and after to really drive home a key point.

Excerpting selected quotes and images

As research continues, but before we formally synthesize the content, we start to excerpt quotes and images from the Selfies that we feel are particularly unique, interesting, or surprising. We highlight the quotes in our utterance spreadsheet, and add them to the Miro board. When we capture imagery from the videos, we pull 10-15 screengrabs in a sequence from key parts in the Selfie. We name them, and keep them organized in the Dropbox participant folder. Our goal is to create a simple, browsable archive of image content that we can use later when we create presentations.

Building mini reels

As the team synthesizes the data and themes, patterns, and interesting behaviors start to emerge, we create mini-reels: videos that include 20-30 second snippets from various participants, threaded together into a 2 minute montage around a topic. These aren’t cinematic masterpieces; they are just the raw videos from the participants, with a quick cut fade between them, and the participant’s name overlaid. It’s precisely the lack of production and polish that makes these reels valuable. We share them with our stakeholders before any final deliverables or formal design and product recommendations are provided, and these reels become the primary way we help our clients and partners see that their customers are not like they are.

Challenges

When we started conducting this form of research, we ran into some challenges unique to the method.

Recording on a phone while doing a task on a phone

During our study, we wanted to observe participants doing an activity online. Unfortunately, many of our participants had only one device—the same phone they were recording the video on! This makes it impossible for them to show us what they’re doing as they do it. We don't have a wonderful solution to this problem; we eliminated tasks that required online activities, and instead had the participants perform these activities during our live Zoom sessions.

Managing a cohort size

When we conduct in-person research, we are typically constrained to two interviews a day: one in the morning, and one in the afternoon. The team could theoretically fit two more into the day, but the realities of travel and fatigue make that unreasonable. This means that a team of two can generally conduct ten in-person 2-3 hour interviews each week.

There’s a similar constraint on a Selfie Study, and it’s based not on tedium or travel, but on the chaos and complexity of managing the prompts. Each new participant adds 10-15 more interactions to manage and coordinate, and it becomes overwhelming very quickly.

The magic number of participants turns out to be five, each completing two Selfie prompts per day. We aim for three cohorts of five participants—for a total of fifteen people—spread over three weeks, with a pre and post interview and four days of selfie prompts. This generates 150 unique participant touchpoints, which is exhausting, but feasible.

Time zones

Digital-only research opens doors to new geographic makeups of participants, and that means managing people in many different time zones in one study. This simple variable adds a tremendous amount of complexity to an already stressed process; now, "send the prompts in the morning" means sending them at 3, 4, or even 5 different times of day. To make sure a participant receives a text prompt before going to work, they need to receive it at about 7am. Researchers on the west coast find themselves sending prompts at 4am Pacific to reach a participant on the east coast, and following up at night is similarly challenging when looking from the east to the west. Again, the spreadsheet is the only way to keep the sending times straight.

Managing unique participant circumstances

Some of our participants work irregular schedules; for example, one of our participants was a nurse and worked the early shift on Tuesday and Wednesday. He needed to receive both prompts at the same time on those days. This means managing another complexity of prompt-sending: making sure we didn’t send him the prompt at precisely the time he asked us not to.

Compensation

When we conduct research in person, we provide compensation directly at the end of the interview, in the form of a Visa or AmEx prepaid gift card that we typically purchase at a CVS or Walgreens. Compensation for our digital-only participants requires an online gift card, and we found that to be particularly challenging.

The various online stores limit the number of cards you can buy in a single day, irrespective of your credit limit. Our credit card's security went crazy when we started buying the cards regularly, and spread across multiple stores. It was only after a call to AmEx that they temporary lifted a security block, which then went back into place the next day. Additionally, we encountered a strange problem, one unique to online compensation: participants had difficulty activating their gift cards from Vanilla Gifts. We played tech support, via Google Chat, and in one case, intermediary between our participant and the Vanilla Gifts customer service team.

Summary

As we describe our process to other people in our field, many point out that there are platforms that are made for this form of research. We've tried many of them, and they just don't work for us. They add overhead for the participants, who already have an intimate understanding of how to use text messaging and their phone's camera. They add overhead for us, because we have to conform the free-form nature of our prompts, and the impromptu changes I described above, to the constraints of the tool. And they don't help with the one thing we really need a tool for: managing the crazy logistics described above. For that, we have Excel or Google Sheets, and as I've come to love video research, I've also come to love a good spreadsheet.

While the bulk of this tutorial focused on how to manage a Selfie Study, it’s worth reiterating why to do a study like this in the first place. Selfie videos are raw and real, and by recording and sharing them, our participants invite us to see the understated beauty, pain, happiness, values, and emotions that make up how they experience daily life. We often speak of participants in a clinical way, like they are necessary parts of our process; even referring to their responses as “data” reinforces that, with the best intentions of establishing empathy, participants are tools. While Selfies don’t remove the sense of participants-as-tools, I’ve found them to be generous gifts from our participants to us, and it’s changed the way I think about research. In some ways, it’s brought me back to the magic of research that I learned 25 years ago: it’s reminded me that design is a service profession, and the intimacy of a shared first-person narrative video of someone’s life reinforces who it is we’re serving, and why.