Chapter Four: Class Interactions

Presentation

Students in my courses constantly present their work.

In an 8 week quarter, they may present as frequently as four times each week; in our 32 week curriculum, that’s as many as 120 presentations. I emphasize presentation for a variety of reasons.

First, a presentation suggests that work that is incomplete can always be shared. Design work doesn’t require a dramatic “unveiling” of a finished product. In my professional work, I’ve observed that this sort of monumental presentation of “finished work” nearly always falls flat. Stakeholders don’t want to be surprised. They want to be brought along through the process.

Additionally, by constantly presenting design work, students build a vocabulary for talking about complex and ambiguous problems and solutions. They become conversant in describing ideas so that an audience can understand them. Non-designers often don’t know how to respond to design work—they may say “I like it” or “I don’t like it.” Stakeholders want to understand design work, but they don’t always have the working vocabulary or internal mental model of creativity to appropriately understand it. They are often looking for someone to help guide them through the work so that they can shape a more refined perspective on it. As students gain a vocabulary for design, they can help an audience better articulate their response so the work can be further improved.

Constant presentation also helps students gain confidence about their abilities. They slowly overcome the idea that their work isn’t worthy of attention, because they constantly have to call attention to it. Students work through shame to arrive at strength.

There are different types of presentations. Students may give a formal presentation, with people sitting in rows watching them orate from the front of the room. It can also be ad-hoc, as someone wanders by, or online through a conference call. But in all cases, the student needs to be prepared to tell a compelling story—to weave a “narrative arc” around the work in a way that makes sense. This means setting the context for the work, thinking about the best format in which to share work, avoiding assumptions about what an audience knows, and then leveraging strong presentation skills to deliver their content effectively.

Setting context

During the first presentation a student gives, they typically fail to set the context for their work. This means that they don’t describe what the assignment was, what their intention was in solving the problem, and what the constraints were. Often, they fail to describe what they did and why they did it, and instead simply show the work. This seems more “honest” to them; they feel that the work should stand on its own.

But design work needs a background narrative to it. Students need to help an audience understand the parameters in which the work was crafted. This means sharing even simple things: what’s the intention of the presentation? Is it to share final design work as a form of celebration? Is it to show in-progress work, and ask for criticism and feedback? Is it to share the whole body of work, or to simply focus on an individual component? Without instruction, an audience will judge what’s put in front of them through whatever lens they happen to have. Students need to set the context for feedback.

After a student presents (typically for the first time), I’ll offer a very pointed critique of their presentation style, not of presentation content. It may look like this:

During your presentation, you jumped directly into the content. You didn’t share who you were, what the purpose of the presentation was, what sort of criticism you wanted, and what you hoped to gain from the presentation. Without telling these things to the audience, they won’t understand how to frame and consider your work. They’ll be left on their own to interpret the context of the work, and that means that you’ll receive a mess of feedback. It won’t be focused, and so it won’t be actionable. On future presentations, make sure you are explicit in setting the boundaries of a presentation. Tell the audience who you are and where you are in the design process. Be clear about what they will see, and why they are seeing it. And make sure to tell them what you hope to learn. Set the limits to critique, describing what is in bounds and what is out of bounds.

This form of direct presentation criticism helps the student begin to take control of their presentations. They realize that a presentation needs to be treated just like any other design problem; it’s about presenting the content through a persuasive narrative. My feedback gives them ways to improve, such as setting the boundaries and context of the presentation.

Presentation methods & skills

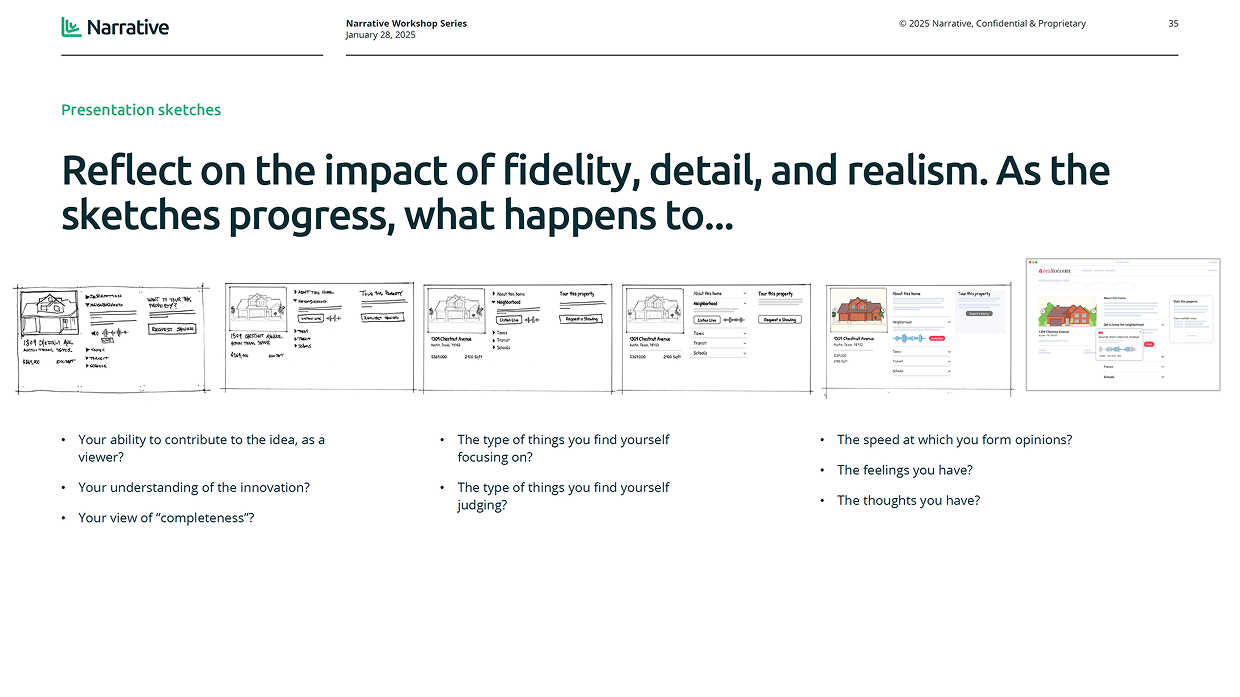

Students typically gravitate towards a Powerpoint or Keynote presentation because they’ve constantly seen other people use these tools. But there are other formats that may be more effective for presenting work. For example, one very effective way to present in-flight design work is to “walk the wall”—gathering audience participants around a working war-room wall and telling both a process and content story. This describes not only what the student did, but also why they did it. Showing sketches, rather than polished slides, helps an audience feel like the work is a draft, and that means they will be more willing to offer their own suggestions on changes. They don’t feel as though the work is completed, and so they don’t feel as though their recommendations will be ignored.

Another form of effective presentation is to use a printed out document as the main set of content. A simple one or two page handout can be used to indicate to a group that the goal is to have an informal discussion, rather than look at finished work. This typically says “let’s start with this content, but I’m open to the conversation moving around.” In this context, the student may be best served using a whiteboard to capture content as it’s discussed. I help students understand that when they control the whiteboard, they control the room. What they write down becomes the frame for conversation, and this is powerful. A simple handout can spark the conversation, and then the whiteboard can be used to guide that conversation.

I teach students raw presentation skills, because I’ve found that they have no idea what to do when faced with the prospect of standing up in front of other people and sharing ideas. I teach both the concepts of a presentation but also the detailed, tactical mechanics of delivering content.

First, I instruct students that every presentation is a chance for them to gain something or lose something. If they present effectively, they’ve gained buy-in or credibility. An audience will leave with a positive view not only of their content but also of them. That’s important in a professional context because ideas live or die based on how people feel, not necessarily based on objective criteria and assessment. If a presentation goes poorly, they’ve lost an opportunity to gain something, such as funding, credibility, acknowledgement, or helpful criticism. Learning that every presentation is positive or negative helps students gain an understanding of the value of the presentation itself, and to treat it as equally as important as their design work itself.

Students also learn that every presentation is a structured conversation, even if they are the only one talking. In a conversation, you don’t just jump into your main point; you work to understand the viewpoint of the people you are talking to, and your ideas intertwine with theirs. A conversation is empathetic, as you try to see what the other person sees and feel what they feel. The dynamics of a conversation are often around sharing an idea or a story. Presentations are the same. As students start to think about a presentation as a conversation, they more actively consider what the audience knows or doesn’t know. They become more aware of their audience.

Typically, when students are starting out, they make poor assumptions about their audience. They forget that the audience probably doesn’t know anything at all about their work. This is particularly true when guests are invited to class. Students will jump right into their content, and the audience will remain puzzled through much of the presentation. Because they don’t know what the student was trying to achieve, they don’t know the limits or constraints that the student worked with during their exploration. And this means that the students will receive all sorts of feedback, most of which is not relevant or actionable. When this happens, the Q&A portion of the presentation inevitably goes sideways, as audience members hone in on details that are less important or less relevant.

For example, a student may have locked down the overall concept design and be looking for detailed feedback on things like font choice or composition. But if they don’t articulate that to the audience, everything is fair game. The audience will probably critique the overall idea, and that isn’t useful to the student; they’ve wasted an opportunity for valuable feedback.

I also teach students that a presentation requires them to feed the energy in the room, and their participants consume that energy. They should leave a presentation feeling proud but exhausted, because it means they’ve put the force of their personality into it. A presentation is often a show, and that means that the audience needs to both understand the content but also feel positive about the decisions they’ve made or ideas they’ve learned. This is reinforced by the presenter’s demeanor. If the student talks slowly and in a monotone, the audience will lose interest and stop being engaged. But if the student is clearly excited about the content, that enthusiasm is contagious.

Part of engaging with an audience is “reading the room.” This is about observing how participants are reacting (are they yawning? are they playing with their phones?) and adjusting both content and style accordingly. In a small group presentation, if people aren’t paying attention, the presenter can gently call this out and can shift the presentation agenda accordingly: “I think maybe this content isn’t resonating as much as I hoped it would. Are there other things we could cover instead that would be a better use of time?” Often, this is enough to bring the room back into focused attention.

When students are just learning how to present, they typically end with “Well, that’s about it.” This is probably the worst way to end a presentation. It leaves the audience feeling a sense of doubt instead of a sense of confidence. Additionally, it leaves the room open to a chaotic question and answer session.

I teach students to end with a more confident summary of what they’ve presented, and to set the stage for the types of questions they would like to address. For example, if they’ve been presenting a new way of thinking about a business strategy, I’ll instruct them to end their presentation by saying, “Today, we’ve discussed the new business strategy I’m proposing. We covered why I think it’s important, and the actionable way we’ll implement it. At this point, I would like to take questions. Specifically, I would like to hear about implementability. Do you feel that this work can be easily implemented?”

This type of ending is valuable for a few reasons. First, it summarizes the content—it helps the audience remember why they are there, and what they should take away from the presentation. It opens the room to questions, but only to questions of a certain type. And it steers the conversation to start with a specific area (can the work be easily implemented?) instead of leaving it open ended.

Q&A

There’s an art to fielding questions from the audience. I teach students to anticipate several types of common questions.

First, a question may be purposefully antagonistic. Working professionals frequently find themselves presenting contentious material to politically charged audiences. Strategic design content may challenge someone’s authority or agenda. So, we practice responding to overtly mean criticism. I’ll role-play an offensive and rude audience member, asking them impossible questions and making statements like “This doesn’t make any sense” or “There’s no way we can do this”, or even “That’s a terrible, stupid idea.” I’ll warn students ahead of time that questions like this may be coming, but I’ll also surprise them. And, when the presentation is over, we always hold a reflection session so the student can describe how they felt and we can critique their response to the question.

There’s another form of question that’s common—the non-question. Audience members will offer a monologue, never actually arriving at a question. Students don’t know how to respond to this form of interaction, so we practice responding to a comment with further discussion instead of an awkward silence. This may be to build on the comment, or to redirect the comment towards the student’s agenda. This reinforces that the student, as presenter, is in control of the presentation experience, but that they need to bring the audience along for the ride.

Sometimes, questions are just not good. Questioners ask about things that don’t make sense, or content that’s already been covered. Students learn to respond positively in these cases, to build credibility, rather than cutting down the questioner. Instead of ignoring the question or shutting it down, they may say something like “That’s a great question”, and then steer the conversation in a positive direction.

Getting prepared

In addition to ending a presentation effectively, students need to understand how to start—how to prepare even before the audience arrives.

First, we discuss setting up the physical space. This includes simple things like removing clutter, organizing the chairs, wiping down tables, and even sweeping the floor. Everything impacts how someone will view and consider a presentation, and most students won’t think about things like this because they are so concerned with the presentation itself. They need to understand the importance of presenting a professional demeanor, even with the workspace.

I also teach students to become aware of their technology. They need to test their laptops with the projector to make sure it works. They need to understand how basic things, like the sound system in the room, work. I reinforce that these things matter: if they don’t understand how the technology works, the audience will lose faith in their ability to design with technology. It’s subtle, but lack of skill in one area can impact perception of skill in another area. Something as simple as trying a laptop ahead of time means they will be prepared to set up quickly and effectively during the actual presentation.

We spend a lot of time talking about emergencies and contingencies. What happens if the projector breaks? What happens if the laptop breaks? Once, I was presenting to a large audience of over 500 people and my laptop decided to reboot itself. I had a choice—I could stand around and awkwardly wait for it to finish, or I could keep presenting. I kept on going. It’s not fair to the ideas or to the audience to simply wait, and I would feel terrible. We practice what to do when that sort of thing happens. During presentations, I’ll sometimes pull the plug on the students halfway through. They need to learn how to proceed with confidence. This prompts a productive group conversation around ways to handle a technical meltdown.

I instruct students to carry backups of their presentation content on a USB stick, on the internet, and on their phone. If they are unable to present from their laptop, they can always present from someone else’s. If they have the presentation on their phone and their laptop breaks, they can use the small slides on their phone’s screen as speaking notes for themselves so they can continue presenting. Our mantra is to “always have a backup.”

We also discuss the details of the slides themselves. First, I teach students that the presentation is for them, not for the audience. This seems counterintuitive—aren’t the slides there so the audience can follow along? In fact, I treat the slides as a signpost for myself so that I know what I want to say and when I want to say it. I can glance at the slide and instantly recall where I am in the overall narrative of the presentation.

This means that each slide has less on it, often just a single word, quote, or picture, and that I know my content cold. It doesn’t mean that I’ve memorized the content, and that’s a hurdle students have to get over. Many have learned (in high school, typically) that practice means memorization, and this is something I need to have them unlearn because a memorized presentation feels forced. And, if there’s some sort of interaction during the middle of a presentation, such as a question from the audience, students who memorize will be thrown off track.

One of the biggest hurdles students need to overcome is reading their own slides. When students first present, they include a lot of text on a single slide, and they then read exactly what they’ve written. When they do this the first time, I stop them in the middle and immediately correct that behavior. I explain to them that reading the slide is rude to the audience. The audience can read it on their own. And, it’s boring to watch. It’s not engaging. Then, I have the student start again from the beginning. This is a hard problem for students to overcome, and I may need to repeat this for several students over the course of the quarter.

Students learn that subtle details on the slides matter. This means simple things, like having pixel-perfect alignment of images, spell checking, and using a consistent font and color scheme. These details add up, and when they are ignored, it can feel like “death by a thousand papercuts.” One of the ways students learn this is by printing out their presentation and critiquing it, just like any other deliverable. We can draw directly on the presentation, circle things that can be improved, and students can iterate on the presentation itself in addition to the content.

Students need to learn not only how to structure a presentation, but also how to literally hold themselves during the presentation. We discuss things like posture and body positions. Where do you put your hands? (Not in your pockets or on your hips) Where do you make eye contact? (With everyone, slowly) Do you sit or stand? Do you walk around the room, or stay planted in one place? These are just like other skills. Students need to learn these things, because no one has ever told them before. To practice and analyze these things, I film the students and then we watch the recording. We analyze and critique the student’s presentation dynamics, focusing not on the content, but on how they present themselves to the audience.